Bioethics Forum Essay

How Bioethicists Can Respond to the Moment by Learning from the Past

Modern bioethics emerged largely as a response to the atrocities of Nazi Germany, including state-sanctioned genocide on an unprecedented scale, cruel experimentation on the vulnerable in the name of “science,” forced sterilization, and systematic murder of the ill, infirm, and “unfit.” As the scope of these atrocities became apparent, we witnessed how technological advances of the industrial revolution merged with the design and operationalization of government policy to create an unprecedented machinery of state-sponsored death and destruction. Out of the aftermath of such atrocities came much of the work and expert consensus building in philosophy, medicine, and ethics that laid the foundations of bioethics, including the Nuremburg Code, Declaration of Geneva, and Declaration of Helsinki.

While many acts taken by the Nazi state are not directly analogous to current events, this history is informative in considering how bioethicists should respond to serious new threats to public health and well-being. In the United States, we now find ourselves in the midst of a chaotic governmental overhaul, as executive orders and actions imperil critical elements of domestic and international health care systems, threatening the health and welfare of millions. Anticipated cuts to Medicaid and CHIP would jeopardize funding for 41% of U.S. births and essential and emergency health care for 79 million American adults and children. Eliminating over 90% of foreign aid from USAID— equating to $60 billion supporting prevention of life-threatening malnutrition in Congo, Ethiopia, Sudan, Haiti, Nigeria, and Kenya; malaria treatment in Senegal; food, sanitation, and clean water for people experiencing humanitarian crises in Columbia, Mali, and Burkina Faso; and essential health services in Afghanistan, Thailand, Syria, Somalia, Bangladesh, and Yemen—is likely to result in widespread preventable suffering, morbidity, and mortality from starvation, exposure, poor sanitation, and infectious diseases.

Threatening to withhold federal research and education grants from hospitals and affiliated medical schools that provide gender-affirming care for patients under 19 years old makes the entirety of inpatient pediatric health care collateral damage in the Trump administration’s war on so-called “gender ideology” and “chemical and surgical mutilation”— terms so inflammatory, hyperbolic, and misleading as to be completely detached from any reasonably valid scientific or medical consensus. Human beings, especially the poor, vulnerable, and marginalized, will suffer and potentially die as a result of these actions. Such policies and ramifications surely entail the most core “issues of human nature, rights, and dignity . . . and practical policy matters,” which Daniel Callahan referenced 10 years ago when he wrote, “good ethics meant working at both ends of a spectrum: a serious grappling with basic issues of human nature, rights, and dignity . . . and dealing with the most practical of policy matters.”

What is the role of bioethics and bioethicists when global and domestic health care politics and policies seem so blatantly unethical?

Some may argue that bioethics and bioethicists should remain politically neutral to maintain objectivity. This stance may fuel tension between the leaders of institutions, who may feel that a public stance of political neutrality and anticipatory compliance best suits the needs of institutions, and bioethicists employed by those institutions, who may feel that remaining politically neutral in the face of unethical health care policies and political actions constitutes a violation of the core tenets of their field–and entails a moral hazard they simply cannot accept if they are to maintain their professional standards and personal moral integrity.

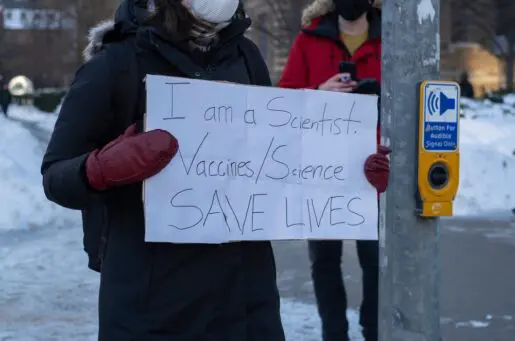

I argue that there is an additional, critical concept worth considering with respect to the role of bioethicists in responding to unethical health care policy, one that is deeply rooted in the history of our field: bioethics and politics are inextricable. The heinous acts committed by the Nazis were generally not a matter of individual bad actors, but of unified, authoritarian state policy implemented to devastating ends. The necessity of modern bioethics arose from the ashes of atrocities committed as a result of malignant political forces mobilizing state machinery and policies to commit mass genocide, sterilization, murder, and cruelty. Our field was born from the need to create expert consensus, guidelines, and principles to prevent future atrocities committed via the weaponization of health policy. This remains the case. Understood in this way, how can we acquiesce to disentangling modern bioethics from the very historical material from which it was constructed?

Through this historical lens, so-called political neutrality in the face of unethical health care policy doesn’t maintain ethical objectivity—it nullifies objectivity by tacitly permitting unethical policies to remain unconfronted by those best informed to question them, limiting dissent, silencing expertise, and creating a vacuum into which the loudest, not the most experienced or best informed, will gladly step. The result is a self-perpetuating sequence of events: policymakers intentionally politicize a health care issue for political benefit, bioethicists remain silent under the guise of objectivity or under pressure from institutions, and politicians encounter no unified resistance from the experts. Allowing political opportunists to effectively remove certain issues from the realm of bioethics is nonsensical—bioethical issues, questions, and dilemmas do not suddenly cease to be defined as such when people choose to weaponize them for political gain. On the contrary, it appears that in many cases the willingness to weaponize bioethical issues is directly proportional to the difficulty of the ethical questions involved, and such cases are those most in need of expert bioethicists.

Faced with these challenges, how can the historical inextricability of politics and bioethics help guide and inform our response as modern bioethicists?

To start, we must recognize the lessons of the past and draw strength and inspiration from them. The struggle of those who exposed the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, for example, can help inform our response to the present. In 1955, Count Gibson voiced his concerns to one of the study leaders, Sidney Olansky, but was rebuffed and advised by senior physicians that pursuing the matter further would damage his medical career. In 1964, Irwin Schatz wrote to Donald Rockwell, another of the study’s senior authors, and was ignored. Between 1966 and 1968, Peter Buxtun, an epidemiologist working for the U.S. Public Health Service (the entity running the study), wrote to the chief of venereal disease at the Centers for Disease Control twice to express his concerns. They were summarily dismissed and the study continued. It wasn’t until 1972, when Buxtun provided information and documents to Associated Press reporter Jean Heller, that the story of Tuskegee broke, public outcry ensued, and the study was formally reviewed.

The story of those who exposed Tuskegee offers three historical lessons we can carry into our actions today.

First, exposing unethical biomedical policies and practices requires both courage and persistence. Second, remaining only within the boundaries of typical academic discourse is unlikely to be sufficient to engage the public and policymakers with pressing bioethical issues. We must also be willing to share our ideas and analyses outside academia, such as in town halls, community meetings, op-eds, and media interviews. Bioethicists are well equipped to translate and distill important bioethical issues into language that people can understand. Third, courage and persistence may entail personal risk.

Gibson and Buxtun both faced threats to their careers if they continued raising concerns about Tuskegee. In our current political climate, bioethicists may face political and institutional pressure to remain publicly quiet and endure threats against their academic and clinical livelihood if they do not. Gibson followed the advice to protect his academic medical career and ceased to express concerns about Tuskegee, but he later regretted his decision. Buxtun persevered despite threats to his career at the Public Health Service. We must decide whether the personal risk of speaking out against unethical health policies, institutions, and systems outweighs the moral peril of allowing them to continue unchecked. Gibson’s regret should serve as a reminder that the moral residue of failing to speak out despite the inclination to use our expertise for the benefit of the vulnerable can linger long beyond the decision itself.

I am not advocating for the use of bioethics to achieve any singular political aim. But there is large gulf between doing that and remaining silent on serious bioethical issues because of fears that speaking out may be construed as “unobjective,” or “outside our lane.” We are tasked with confronting bioethical issues and providing reasoned guidance, and whether the outcome of such an inquiry falls on one or another side of a political spectrum is irrelevant to the question of whether an action or policy is ethical. Our expertise compels us to speak, write, and act when confronted with bioethical concerns and crises, and to do so in a way that reaches the greatest number of those impacted by these issues. To abdicate that responsibility is to sever modern bioethics from its very reason for being.

Michael Certo, MD MA MM, is an attending physician and ethicist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. The views expressed here are solely those of the author. @mikecertomd.bsky.social

Thank you for this cogent, compassionate, and useful perspective and advice…