Bioethics Forum Essay

De-extinction is Here. Now What?

On April 7, Colossal Biosciences, a biotechnology company co-founded by George Church, a leading Harvard and MIT geneticist, announced that it has achieved a scientific first – bringing back an extinct animal: the dire wolf. Media outlets have quickly hyped the event, with pictures of small, cuddly, adorable white cubs.

This report follows on the company achieving, in March 2025, a key first step in its goal of bringing back the extinct woolly mammoth – altering genes to create a woolly mouse. News organizations similarly displayed images of a cute rodent with gobs of blond hair – evoking Mickey Mouse’s innocence and Marilyn Monroe’s flamboyance.

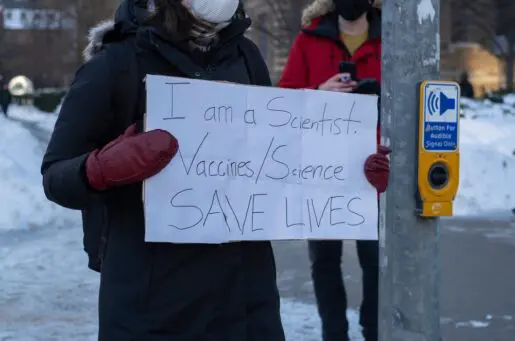

Advances in gene editing technologies, especially CRISPR, are giving us extraordinary new tools to resurrect certain animals and even create new species, but should we do so, and if so, when? The 1993 film, Jurassic Park, showed scientists generating dinosaurs for a zoo, and producing horrific results, with the beasts soon attacking their modern creators. Crucial questions emerge about whether such de-extinction reflects mostly scientific hubris and playing God with cool new technological toys, or something more valuable.

Recently, human activity has extinguished many species whose natural habitats nonetheless remain intact. If resurrected, these creatures could potentially return to the wild and survive.

But the ecological niches of most extinct creatures, like the mammoth, have vanished, raising concerns about what areas these animals would inhabit, and whether they will suffer or flourish, and/or harm other, existing species.

Over millions of years, the woolly mammoth, for instance, evolved to endure the cold, roaming the icy tundra of what is now the American Midwest and other frigid regions. But around 10,000 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, almost all these animals perished as the earth warmed and human hunters appeared and spread. Today, vast farms growing corn, soybeans, and wheat occupy the mammoth’s former lands. The Arctic is shrinking, already imperiling polar bears. If mammoths return, where and how will they live? Will they decimate other species and/or succumb to strains of viruses and bacteria that did not yet exist in their era?

Classified as hypercarnivores, dire wolves grow to around 150 pounds and could readily kill cattle, horses, birds, squirrels, and house pets. When their less carnivorous relatives, red wolves, were introduced into Great Smoky Mountain National Park in 1987, they soon suffered from Lyme disease and other infections and faced competition from coyotes and other animals. With insufficient prey inside the park boundaries, they wandered outside up to 40 miles away to kill animals in surrounding areas.

Colossal Biosciences has also produced red wolves, stating that only 20 members of this species reside in their natural habitats, yet almost 300 red wolves in fact already exist and readily reproduce in captivity. Conservationists have repeatedly tried to reintroduce them into the wild, but humans have interfered. In North Carolina, for instance, they were reintroduced only to be hunted and killed by humans, since the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service did not enforce regulations that bar such poaching.

Various human efforts to introduce species into existing ecosystems have caused disaster. In 1935, Australians introduced cane toads to eat beetles that infested sugar cane crops. But these reptiles emitted poison that soon exterminated other species. Likewise, enormous Burmese pythons have taken over the Florda Everglades, where they were inadvertently introduced, decimating rabbits and other animals.

Colossal has the three dire wolves confined to a 2,000-acre preserve (around 3.2 square miles), but wolves usually take a hunting territory of 50 to 1,000 square miles. We could simply put de-extincted animals in zoos, but animals there, cramped in cages or with severely limited areas to roam, face numerous stresses, and may suffer, despite efforts to care for them well.

The reproductive technologies used in de-extinction, such as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) or cloning, can also cause harms. These processes entail injecting a genetically engineered cell nucleus into another cell to create an embryo, but they may pose risks of cancers or other serious medical problems in the resulting organism.

Moreover, while the company claims to have brought back an extinct animal for the first time, the creature produced in fact instead appears to be “like” a dire wolf, with many, though not all of the DNA identical. The company used 15 edited dire wolf genes, but not others. Yet a gene may perform more than one role in the body and operate in tandem with other genes. Such multiple gene alterations may have unintended consequences. We would not, for instance, want to create “super wolves,” more voracious than others.

In addition, the company, valued at $10 billion, is presumably spending tens of millions of dollars on de-extinction that could instead more fully assist conservation efforts to save endangered animals on the verge of extinction. President Trump’s cutbacks at the Environmental Protection Agency and his desire to open federal lands to drilling will jeopardize many species. Techniques developed through de-extinction efforts may help in devising ways to reduce human disease but, especially given major cuts to vital areas of research at the National Institutes of Health, these funds might instead be used more directly to discover treatments.

The baby wolves and mice certainly look cute. But as with humans, we should aim not just to produce adorable infants, but seriously consider their future – whether, where, and how they will survive and thrive.

Robert Klitzman, MD, is a professor of psychiatry at the Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons, director of the Bioethics Masters and Certificate Programs at Columbia University, and a Hastings Center Fellow. He is the author of Designing Babies: How Technology is Changing the Ways We Create Children. @Robertklitzman @RobertKlitzman.bsky.social LinkedIn Robert-Klitzman

[Photo: Colossal Biosciences]

Whether or not a species can be brought back from extinction, and the ethical implications of doing so, is a matter of legitimate discussion. But let’s be clear: Colossal did not “resurrect” the dire wolf. They introduced base pair changes into a handful of genes to make the grey wolf appear more like the dire wolf. Millions, not tens (or even hundreds, if “gene edits” refers to the modification of whole segments), of base pair changes would have to be made in order to resolve the genetic dissimilarity between the two species.

Articles like these should really make these distinctions clearer in their titles and leading paragraphs. The twelfth paragraph contains the central point here, and I’m afraid that the casual reader wouldn’t even catch it at all.