Bioethics Forum Essay

Myopic View of Xenotransplantation

The news media significantly influence public perceptions of medical innovation. How cutting- edge medical innovation is presented—what receives attention and what does not receive attention—is ethically relevant. A report last week in the New York Times of a pig heart transplant performed at the University of Maryland Medical Center exemplifies a common myopic view of xenotransplantation research. The article describes the case of a 58-year-old Navy veteran with end-stage heart disease, too sick to qualify for a human organ transplant, who received instead a genetically modified pig heart—the second patient to undergo this experimental surgical intervention. The patient appears as a heroic volunteer, helping to advance science in the hope of a long shot at extended survival.

The innovative nature of xenotransplantation gets prominent attention. In a breathless tone, the article’s author writes, “In recent years, the science of xenotransplantation has taken huge strides with gene editing and cloning technologies designed to make animal organs less likely to be rejected by the human immune system.” The pig donor, supplied by the for-profit company Revivicor, had 10 genetic modifications. The patient also received an experimental antibody treatment. In general, the news media approaches xenotransplantation as an irresistible technological frontier—one that is driven by scientific curiosity and prestige, and the potential of substantial future revenue flowing into biomedical companies and transplant centers.

As is typical of news stories concerning xenotransplantation, this article draws attention to the more than 100,000 Americans on the transplant waiting list, most of whom are seeking a new kidney. However, only 25,000 kidneys are transplanted in the United States each year. No effort is made to place this set of facts about organ donation and transplantation into a population health perspective. Of course, it is lamentable that approximately 6,200 Americans die each year while awaiting an organ transplant. But this represents only 0.2% of the approximately 3.2 million Americans who died in 2022.

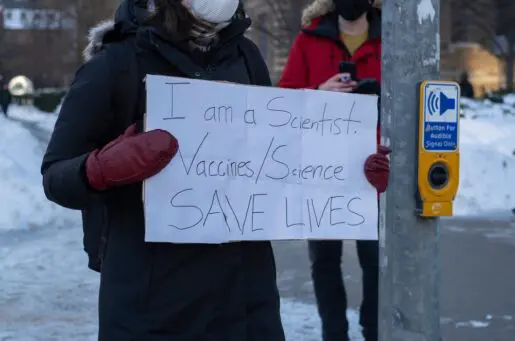

Moreover, no mention is made of the prospect of preventing end-stage chronic disease, which in the case of kidney disease gives rise to the need for expensive and burdensome dialysis and organ transplants. Preventive efforts include enhanced educational and policy interventions to promote healthy diets and lifestyles and greater uptake of drug treatments to control hypertension and diabetes. Although lacking in scientific prestige, the fascination with technological innovation, and the prospect of substantial profit, promoting prevention holds promise for reducing the incidence, or ameliorating the progression, of chronic diseases.

The New York Times article reports that the Food and Drug Administration gave “compassionate use” emergency approval for this xenotransplantation intervention. But there is no mention of the compassionate alternative of palliative care and whether this was explored with the patient and his family.

Also noteworthy is the absence of any mention in the article of the ethical issues associated with the exploitation of pigs, who are intelligent animals, for the sake of this cutting- edge research and innovative treatment. Prior and ongoing pre-clinical xenotransplantation research has also involved transplanting pig hearts into baboons. And the FDA has stipulated that investigators must keep a large number of primates alive for at least six months after transplanting pig organs as a prerequisite to permitting clinical trials in humans .

Success in xenotransplantation would represent an impressive feat of human ingenuity and technological prowess. However, if transplantation of hearts from genetically modified pigs proves viable—a big if—it would, at best, be a mixed blessing. Patients with end-stage heart disease who are unable to receive a human heart transplant would experience prolonged survival, although they might not fare as well as patients who receive a human heart. All transplant patients must take powerful immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of their lives, and these drugs cause vulnerability to serious infections. Some patients on the transplant list might face the agonizing decision of whether to continue waiting for a human heart, at risk of further deterioration, or opt for a genetically-modified pig heart transplant. If xenotransplantation becomes a validated treatment, it will be very expensive. From a societal perspective, would the investment in research and implementation into clinical practice be cost-worthy?

Bioethicists for the most part have not questioned whether xenotransplantation ought, from an ethical perspective, to be pursued, all things considered. Instead, they have focused on how to regulate, ethically, research and development of this exciting innovation. Regardless of the ethical issues it poses, experimentation with xenotransplantation to address the shortage of human organs for transplantation is proceeding full steam ahead. My aim here is not to argue for rejecting xenotransplantation. Rather, I suggest that science journalists and bioethicists should approach xenotransplantation with a wider lens. Worthy of greater attention are reflection on whether the potential benefits of xenotransplantation are worth the costs, promoting effective measures to prevent chronic diseases that give rise to the need for transplantation, as well as the challenging question of whether the promise of xenotransplantation justifies the harmful treatment of pigs and baboons in pursuit of this innovation.

Franklin G. Miller, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Ethics in Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College and a Hastings Center fellow and board member.

[PHOTO: University of Maryland Medicine]

Thank you so much Dr. Miller for powerfully articulating the need for a wider lens to be focused on xenotransplantation.

Thank you for your thoughtful piece. Why quality of life is not as central to these discussions as extension of life, I don’t understand. Especially the patient should be very clear on the difference in quality of life after surgery versus during palliative care – otherwise he has not truly given informed consent. And, as you well point out, society should be clear on the difference in quality of life when preventive health measures are funded and practiced and when they are not – this is the area I work in and daily realize how little some of my neighbors know about the need for more investment in primary and preventive health care measures. And if we believe in animal rights, which would make us more empathic creatures ourselves, we would at least be more grateful to the pig (if not offended by its lack of say) in this process.

Thank you Dr Mille! Similar views are expressed by the Swedish National Council for Medical Ethics in a recent statement,

https://smer.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/yttrande-om-xenotransplantation.pdf

Miller’s article is iconic for the direction bioethics needs to move, away from moon-shot medical experiments to greater focus on public health, population health and stewardship of resources, which are increasingly limited. We need more of this kind of thinking.

Great article, I agree that the ethics of xenotransplantation needs serious evaluation. Even the language we use – like falsely calling the pigs “donors” – serves to obscure the reality of what xenotransplantation requires. I could not agree more that we must view this topic with a wider lens.

This article described how the media has emphasized the cutting-edge aspects of xenotransplantation while neglecting the bioethical dilemma that this topic opens up. This article sheds light on the media’s tendency to spotlight the groundbreaking facets of xenotransplantation, often at the expense of fully exploring the intricate bioethical dilemmas it presents. One such dilemma is the balance between population health and individual treatment. The media highlight individual cases of organ failure and high-tech treatments available but overshadow the importance of public health strategies such as disease prevention and lifestyle intervention. Another major ethical concern is the patients themselves, who face the ethical dilemma of having to choose between waiting on an extensive waitlist for a human organ transplant or opting for xenotransplantation, knowing the higher risk of death involved with the latter. Patients facing life-threatening diseases and conditions where conventional treatments have failed are desperate, and this can impact their decision-making. This prompts me to question: Are these patients susceptible to coercion, or can informed consent for experimental treatments like xenotransplantation truly be considered ‘compassionate’?

Thank you, Dr. Miller, for this insightful article! I appreciate how this article brings into light several issues that I don’t usually see discussed when it comes to discourse organ transplants. First off, I think evaluating the ethics of using a pig’s organs is a very interesting subject, considering that, while pigs enjoy the status of being agricultural animals in the US, and therefore, often safe to raise for consumption (which comes with its own horror stories), they are also very intelligent animals who may well deserve the type of respect that one would afford human subjects. Of course, combining this with other intelligent animals who are not considered agricultural animals (i.e. the baboons mentioned in this study) makes the issue of expanding considerations of principles such as beneficence and non-maleficence beyond human populations. Beyond that, I thought that looking at the issue of organ transplants, in context of the entire health situation within the US a good way to contextualize the state of the organ transplant situation, as well as looking at preventative care, which can also play a role in reducing the need for transplants in the first place.

This piece does a fantastic job of highlighting the harsh reality that media attention can drive the focus and progress of research, for better or worse. Novel technologies and procedures do seem to generate more attractive headlines which drive revenue and shape public perception. While some of the more practical ethical issues related to xenotransplantation may eventually be addressed with advances in things like in silico testing, the question of whether “solving” the ethical questions of xenotransplantation ought to take precedence over less novel and more pragmatic preventative approaches remains largely unaddressed. The idea certainly has some degree of merit, but an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Thank you for the thought-provoking article!

Thank you, Dr. Miller, for this incredibly thought-provoking piece. A key issue that also frequently goes underexamined is the ethics of how certain types of research studies get funded more than others. As you rightly point out, preventative medicine is often ignored when placed side-by-side with shiny, attractive technological advances like xenotransplantation. It is a known fact that public health in the United States is horrifically underfunded, to the great detriment of its own population. Preventative health measures have solid data supporting their efficacy and relative cost-effectiveness, and yet this evidence does not appear to be convincing enough to drive sustained interest and support from both the public and the private sectors for its funding. Instead, money is poured into a pig heart transplant, which at best has questionable long-term outcomes.

The problems only become thornier when we consider that industry-funded research continues to grow, especially in light of the current political situation putting government-funded research in flux. Industry funding introduces conflicts of interest that are harder to mitigate and regulate, and one of these conflicts is industry’s end-goal of increasing revenue. Preventative measures, while cost-effective and proven, are not as profitable as newfangled treatments that promise more instantaneous effects (such as the GLP-1 medications now popularized for cosmetic weight loss).

The truism “follow the money” applies here: whatever study gets funded gets more attention, and it’s a self-perpetuating cycle. In order to stem this cycle, I think policymakers should explore the idea that it is ethical to sometimes deny some studies the funding in favor of other studies that serve more people in a more cost-effective way. In a country so addicted to shiny new technology like ours, this may be a controversial take, but it will ultimately serve to better more lives, even if that effect remains largely unrecognized by those who reap the benefits. This especially applies if the funding in question is from a public source.

I appreciate how this piece highlights the power of media to shape public perception of medical science and technology, which is frequently dichotomously misapplied for the vilification or lionization of some advancement rather than harnessed to educate people about its nuanced scientific and ethical implications. The ethical issues surrounding xenotransplantation (X-TX) are so apparent, though, that their exclusion from the Times article cited seems deliberate. Even if X-TX is refined to the point of medical success—which is still a long way off—we need to question whether this end justifies the means (i.e., the measures used to research X-TX robustly).

The almost ironic designation of “compassionate” for the transplant described prompts us to consider what “compassion” really is in clinical care. I agree that in this case, for a patient too sick to qualify for human organ transplant, given the risks of xenotransplant, that palliation and end-of-life care could be more compassionate. However, one question I still have is how or to what extent providers should reconcile compassion with respect for autonomy? Intuitively, I feel that compassionate care is not necessarily synonymous with prolonging life, especially where the anticipated quality of life is low; nevertheless, if all options are presented, and the patient, expressing a fear of dying, requests that all life-sustaining measures be pursued (with little likelihood for quality life), is it compassionate to agree to this simply because he asks? Or is compassion necessarily and solely tied up with the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence? Or some combination?

Regardless of whether the option was explored with the patient and his family in this case, I think the New York Times article missed an important opportunity to write about palliative care and what it entails, so that readers might be encouraged to reflect on what they would want their end of life to look like. And, in addition to palliative care, I think that compassionate care would extend to promoting health before the onset of disease; perhaps too often, we are focused on developing technology to mitigate the consequences of uncontrolled disease, rather than investing in preventative measures or addressing the social determinants of health that often result in ailments that progress to end-stage organ failure.

I also agree with Dr. Miller’s point in the last paragraph: that bioethicists need to evaluate whether xenotransplantation should be pursued at all. Examining how this research ought to be regulated can play a role in this assessment (i.e., inasmuch as this enables us to see whether the enterprise *can* be sufficiently regulated), though not a sufficient one. One question is whether it is appropriate to offer X-TX for clinical use (even under emergency categories) when it is not well researched; moreover, we might question whether at this stage we can even separate clinical from research applications.

The risks of harm with X-TX are substantial and currently outweigh the benefit of prolonged life. Harm includes the possibility of hyperacute rejection (due to species discordance, which increases with evolutionary divergence) as well as the transmission of zoonotic disease (e.g., porcine endogenous retroviruses, or PERVs). These diseases might even persist, or have delayed presentation, in individuals who use xenotransplant as a bridge to allotransplant, which might require long-term clinical monitoring as a safety measure. It has also been argued that the nature of xenotransplant research is in violation of internationally recognized standards of ethical research, particularly with respect to the right of participants to withdraw from studies at any time. Though it would be impossible to withdraw in the sense of undoing the xenotransplant (and its potential health risks), there is also a question of whether it would be ethical to allow participants to refuse to submit to follow-up. This is because of the potential of zoonotic infection to be transferred among humans, leading to public health concerns. Is it possible to irreversibly waive one’s right to withdraw from research participation?

The extended surveillance might constitute a privacy violation, insofar as transplant recipients may be required to report any signs of unexplainable illness and close social contacts that may be at risk of acquiring infection. Whereas allotransplantation only requires the consent of the recipient and the donor (or a representing surrogate), would X-TX, with its potential public health implications, require majority or unanimous societal agreement?

I’m not sure of the likelihood of this, but in the event that zoonotic disease spreads widely among humans, we might need to consider the ethical dilemmas that would manifest on a global scale (e.g., possible pandemic). In particular, this raises concerns about global justice inasmuch as lower-income nations—which would be less likely to gain from X-TX (given the costs of the procedure and inequitable distribution of healthcare)—would shoulder a disproportionate amount of burden due to insufficient medical resources and infrastructure to combat the spread of disease.

Other justice concerns also exist. Pig organs are seen as suitable for X-TX based on their size, as well as more widely held convictions about the wrongfulness of using non-human primates for this. However, certain religions (Islam, Judaism) forbid the consumption of porcine products, based on the belief that pigs are unclean or taboo; along these lines, members of these faiths might not be able to benefit from X-TX (imagining that, at some future point, this intervention could confer substantial medical benefit). Would they then be given higher priority to receive human-donated organs? Regardless of how advanced xenotransplant becomes, it will likely not match or exceed human-to-human transplant—is this then an injustice?

We might also consider whether X-TX would be offered to pediatric patients. Parents may consent to organ transplant on behalf of young children without decisional capacity; however, given the aforementioned issues related to consent and X-TX for adult patients, it seems unreasonable to allow parents to consent to X-TX for their children. Can parents waive their child’s right to withdraw from research follow-up, and, if so, could this be sustained into adulthood?

Finally, we need to consider that—even if the medial risks and potential distribution injustices were managed such that X-TX provided patients with a longer, higher quality life—is there still *something inherently wrong* with xenotransplantation? In particular, I think we need to grapple with the moral status of animals, and whether they have significant enough interests to warrant factoring into any harm-benefit calculation. It is important to recognize that, though many would object to harvesting organs from non-human primates, these animals are still used in X-TX experiments to test the safety of transplanting orans from genetically modified pigs (as a proxy for pig-to-human transplantation). We should also question whether it is ethical to breed and slaughter pigs to increase organ supply. Killing pigs for consumption is not uncontroversial, but even if it were definitively morally permissible, this does not necessarily justify killing pigs for other purposes (e.g., harvesting their organs). (An analogy might be that many meat-eaters object to killing animals for their fur.) One might also object to this practice because of the conditions the pigs are subjected to in order to become suitable donors: to minimize the risk of transmitting infection upon transplant, the modified pigs are bred and housed in sterile, isolated conditions, which precludes social interaction and fulfilling natural behavioral tendencies. This can compromise animal well-being, particularly in animals, like pigs, known to be social and highly intelligent. The use of animals in biomedical research is also ethically constrained by the 3Rs (replacement, reduction, refinement). But X-TX can be argued to be in violation of “replacement” because it permits us to forgo investing in better therapies to treat organ failure or strategies for illness prevention.